Just a quick note to say that I’ve added an events page to the top of the blog. Hoping to keep this ticking over – I’ve really enjoyed spending so much time this year with Flashtag, Bad Language, Verbalise, Dreamfired and book groups. Good peoples, one and all.

Tag: reading

Notebook

On the rare occasions I’ve been asked for writing advice, one of the things I always suggest is to carry a notebook and a pen. I’ve lost count of the thoughts, ideas, plots, characters and dialogue I’ve let slip through the gaps in my atrocious memory. It’s heartbreaking. I took to carrying a pocket notebook years ago. Sometimes I fill one in a month, and sometimes in six months, until it disintegrates to dust and fibres and I need to tape the spine. I keep them all on a shelf above my desk. Once, while backpacking in Australia, I spilled a hipflask of Maker’s Mark all over my notebook, and the whiskey erased the ink. I lost my bourbon, and I lost weeks of passing thoughts. As my friend Ali said, it was the very definition of two wrongs not making a right.

Notebooks aren’t just for the utility of capturing ideas. It’s important to remember how to write the hard way. I’m a thug of a typist, but I’m pretty fast, and I spend a huge amount of time glued to my computer, whether that’s writing or editing. My default setting is electric, and when I have an idea, I tend to go to the computer first.

This is all relevant because I’m finally dipping my toes back into The Hollows. I started on Christmas Eve 2013, wrote sporadically through the new year, and hit 25,000 words around June. I haven’t worked on it at all since then, but last week I finally had the space to look at it again. On reading it through, I was a little unhappy with some of my work. Parts of it read well, but simply weren’t right for the story any more. No matter how much I shuffled chapters or copied and pasted paragraphs to try and make it fit, the story wouldn’t gel. Instead, I put on some music and sat back with a fountain pen and an old office diary I nabbed years ago to use as a notebook.

The diary was a red hardback day-to-a-page thing, brand new and unused from 2006, a ribbon bookmark folded flat between the crisp blank pages. It was perfect. I started scribbling down my worries and woes. I made lists of characters I liked and characters I didn’t need. I wrote down what worked, and what never could. I drew lots of dots and stars and arrows connecting things that wouldn’t make sense to anyone else. I wrote questions and answers. I wrote until my hand hurt and I had a dent in my forefinger. A few hours later, the mist was beginning to clear, and some new ideas were beginning to show themselves.

That night, I talked it through with Mon. She’s so good at giving me space to shape my ideas. Often the act of explaining a story to Mon explains the story to me, too. Vocalising something gives it clarity. After chatting it through, I spent another hour or two jotting down new ideas, new people, new places to explore.

This is all the planning I do when I’m writing. Rough notes and loose association. It works better with ink than on a screen. It makes the process tangible. I couldn’t do what Ali did with his last novel, and write the whole thing longhand – that wouldn’t work for me – but I’d forgotten how healthy it is to make a mark, to scribe into the fibres of the page. The act of writing with a pen has conjured new ideas, too – things that couldn’t have occurred in pixels.

The hardest part is making the decision. I went back to the manuscript, and cut 11,000 words. It hurt, but it was important. There were good scenes in there – good chapters – but they’d sent me off course, and they had to go. Now they’re gone. My draft is 11,000 words lighter, but I’m more confident in what is left. The shape of the story has changed. The characters are starting to stir, beginning to show themselves.

It’s insane to think I’ve achieved so little since starting it almost a year ago. I feel like I should have a finished draft by now. I know, looking back, that we’ve been extraordinarily busy this year, and that I’ve completed a multitude of other things, but The Hollows is back in my life and shouting louder than ever. I’ve spent some time on the wrong path, but now I think I’ve found my way. A pen, a compass.

Self-publishing

Natalie Bowers, editor of the excellent picture/fiction mash up site 1000 Words, has written a wonderful review of Marrow. It’s always fantastic to have a reader completely get my stories, so I’m really pleased to share her thoughts on the collection.

After reading the book, Natalie asked me to write a little about why I decided to self-publish Marrow. If you’re interested in traditional vs. self-publishing, then lay on, Macduffs, and discover why I chose to take that path.

This is a picture of my daughter and I arguing on a path.

In The Flow at Sprint Mill

A few months ago, I was asked by my friends in the Sprintmilling art collective to run a spoken word evening as part of their exhibition for the excellent C-Art open studio trail. My first instinct was to say no, because I’m so constantly swamped with work that I’m barely writing anything of my own. But on reflection, I decided to go ahead and give it everything I had. I’ve never organised or hosted a spoken word event, and Sprint Mill is a very special place to me. What swung it for me was a request of mill owner Edward Acland, who wondered if the performers might be interested in writing a piece or two inspired by the mill. I was so intrigued by this idea that I decided to take it on. I called the night In The Flow, and set about inviting writers I knew would do it justice.

In the end, we had a stellar line-up, including the slam-winning poetry dynamo that is Joy France; Guardian weekly pick BigCharlie Poet; Poet Laureate of the Tripe Marketing Board, Jonathan Humble; journalist, poet and painter Helen Perkins; poet of internal, external and emotional landscapes, Harriet Fraser; the frighteningly talented young Turk of the macabre, Luke Brown; Edward Acland himself; and me.

All the writers rose to Edward’s challenge, and all attended the mill at various points for inspiration and ideas. The place is soaked in stories. Sprint Mill is a wonder. It is both serene and madcap, combining perfect sense with complete bamboozlement. Over three floors, scores of chests, cabinets and workbenches line the walls, all laden with jars, boxes and objects. It’s no less than a portal into another time. The ceiling is lined with skis and 1950s shop signs. The windows gather dust, discarded toys, wood swarf and cobwebs in rafts. Military buttons sit beside bradawls and buckets of rusty nails. Washing machine parts are pinned in loops to a heavy magnet – an apothecary cabinet groans with esoteric contents, all neatly labelled: barbershop equipment, bird eggs, lightbulbs. The mill is a bipolar rabbithole of wonder and nonsense. Every time I visit, I find myself caught between poles of melancholy and childish joy. It’s a tangible place, and it’s a dream.

I didn’t hear or read any of the writers’ responses to the mill until the night. Somehow, between introducing the acts and reading a piece from The Hollows for the first ever time, I managed to film them at work. Here are the performances in order of appearance. Enjoy…

Edward Acland distills his decades of collecting into The Jars:

*

Jonathan Humble reads bombastic ballads of tripe, Daleks, and reckless rhubarb:

*

Helen Perkins performs three pieces, finishing with the utterly enthralling Edward’s Gunshop, which is one of the best poems I’ve heard for a long time:

*

Luke Brown reads a brilliant (untitled) short story of chaos, catastrophe and common sense. Fans of Roald Dahl and Jeremy Dyson in particular will devour this:

*

Harriet Fraser charts the life of a seedling, considers cagmagery and takes us into the nether regions of a sheep:

*

BigCharlie Poet delivers mouses, houses, foxes, and his Guardian pick-of-the-week, It’s The Grit That Makes The Pearl:

*

Joy France finishes the night with a wonderful sequence of poems touching on memory, loss, joy, patchouli oil and fracking:

*

There were more than thirty of us crammed into a smaller section of the mill, ruddy with stovelight and beer. We sat on hand-carved chairs and recovered benches, and dust crawled in columns from the ceiling. We laughed, we talked, we drank and we told each other stories. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, but words mean nothing without the folk to hear them.

Art Is Long, Life Is Short

After years of occasional submissions, I’m delighted to report that the outstanding spoken word night Liars’ League London finally accepted one of my short stories. For those that don’t know, Liars’ League has grown into one of the finest story nights in the country (now with branches in Leeds, Leicester, New York and Hong Kong) by using professional actors to read stories. Or, as they rather more succinctly put it:

Writers write. Actors act. Audience listens. Everybody wins.

When I first started writing short stories, what feels like a century ago, I experimented relentlessly with different voices and techniques. Over the years, I’ve moved away from straight-up literary fiction and towards the modern genre fiction that I prefer to read myself. In doing so, my writing has become, to me, more believable; I believe my own stories more than I used to. At the same time, for reasons I’m still brewing on, most of my story narrators have become female. This wasn’t a conscious decision. It happened organically as I drifted happily into low fantasy and magic realism. When I thought of The Visitors, I always knew Flora would be Flora. In my current work-in-progress, I always knew Kerry would be Kerry. I have my next four or five novels blocked out, and they all have female narrators, because they could only have female narrators. That’s just the way it is.

The Liars’ League story is called Art Is Long, Life Is Short. It’s one of my oldest unpublished pieces, and one of my favourites. As one of my older stories, I wrote it with a male voice. I imagined someone like Larry Lamb. A grizzled gentleman of the world – a Cockney – down on his luck and pouncing on a break. A male actor was booked to read the piece, and I was delighted to be a contributor to Liars’ League.

But – with a week or so to go – they contacted me to say that the actor had to cancel. Would I consider an actress instead?

YES. Yes, I’d consider that. On re-reading the story, I was amused to notice that there isn’t a single marker of gender – and the more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea. Actress Carrie Cohen shows why Liars’ League were absolutely right. She reads better than I’d thought possible, and I’m really, really pleased. She embodies the character with humour and pathos, and the story works far better with a woman than a man. It’s a thrill beyond measure to see it all brought to life.

There’s something else, too. I loved giving the story away. It’s not mine anymore. It belongs to Carrie, and the audience, and that’s incredibly exciting. Having spent years sitting on a piece that I thought had some merit, it’s wonderful to share it out – to see it adapted, altered and ultimately evolve from my wee idea into something bigger.

So here it is. Please enjoy Art Is Long, Life Is Short, read by the wonderful Carrie Cohen:

Not The Booker

I’m cautiously delighted to say that The Visitors has been shortlisted for the Guardian’s Not The Booker prize. It’s been a rather bruising process to get this far. The longlist was very long, featuring a hundred novels. Not The Booker is infamously decided by public vote, which leads to all kinds of hijinks from authors, publishers and agents drumming up support. That’s a hundred clusters of psychic tension detonating online simultaneously. No wonder things get heated.

I was in Greece for the first two days of the week-long voting window, by which point there were already clear leaders. With five days to go, I started doing what most of the others had done, and announced my part in the longlist as loud and far as I could. I was fortunate that a lot of people who’d read and liked The Visitors voted for me, and I managed to reach the shortlist. I’m extremely thankful and humbled by the support for my book.

The shortlist holds some intimidating competition – genuine literary titan Donna Tartt, no less, as well as Louis Armand, Mahesh Rao, Tony Black and Iain Maloney. I’m a little concerned that The Visitors seems to be the only work of genre fiction on the list; I’m worried it won’t be deemed worthy enough. And now I’m actually up for review, there’s the prospect of this sort of evisceration at the hands of Sam Jordison, too. Ouch. All in all, I’m expecting dark things from the Guardian readers – which begs the question: why bother entering?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately. The first time my agent and I went to meet my editor at Quercus, we discussed the importance of promotion and self-promotion. It’s simply a mandatory part of an author’s life, now – especially a debut author. Publishers are spread thin. They can’t afford to spend time plugging new writers, and that means new writers have to plug themselves.

It’s unfortunate, then, that I’m not great at selling myself or my work. I feel embarrassed at intruding on other people’s time, and I despise arrogance so much in other people that I cringe at anything that could make me seem arrogant. It took months of goading by my wife before I summoned courage to introduce myself to my local library and local Waterstones. On both occasions, I fumbled through a minute of apologies before finding a way to explain who I was, that I had a book out, and that I wanted to say hello. They were perfectly nice, and keen to discuss running some future events, but the process leaves me feeling weird, and even a little cheap.

If I’m ever going to find a way to write full-time – or, being more realistic, to better balance my life and jobs around writing – then this is the sort of thing I need to do. As my Dad says – you’ve created a product, and now you need to sell it.

Books are products, for sure. I think stories are far more than that. Books are the vessels that carry stories, though, so maybe I’m splitting hairs. I know that I want to write stories, but also that I don’t really want to sell my own books, because it makes me feel so uncomfortable; I know that I want as many people as possible to read my work, and that selling my own books, and selling myself, is one of the only ways I can find to keep writing my stories. For most writers, that’s the binary pair of modern publishing.

When I try to reconcile these two distinct strands of my industry, I have to accept that all I want to do – what I wish for every day – is to write full-time and get these stories onto paper, into people’s heads, into people’s hearts. Whether I like it or not, that means playing the game.

I don’t know how it’s going to go, but my money’s on Tartt or Black.

Weird days. Remember Remember have been helping:

The slow life

Another year, another holiday. A fortnight before our wedding, and with a thousand things to organise, Mon and I have taken Dora for a week on Kefalonia in the Greek Ionian islands. Some people thought we were crazy, leaving so soon before the big day, and others thought we’d done exactly the right thing. It’s been wonderful. Our studio was cheap and cheerful, but had stunning views of the sea. The beach at Lourdas was only a few minutes away. We’ve done as much sunbathing as Dora would allow, and spent the rest of the time building bad sandcastles or splashing in the shallows. We visited Melissina cave, where they filmed The Goonies, and drove round onto the Lixouri peninsula to the secluded beach cove of Petanoi, ringed with sheer white cliffs.

Kefalonia is intoxicating. Olive trees spill into the verges, and fig trees grow in long-abandoned lots. The cliff-top hairpins are graffitied with faded communist slogans. Goats dawdle as they cross the road in scraggy herds. Each of their bells is tuned slightly differently, so the goatherd knows where each animal is foraging. When they’re hidden by the pines, the bells sound like secret orchestras, playing just for you. Skinny feral kittens bat at grass stalks and dry leaves. Cacti grow on roadsides. Beehives, painted rainbow bright, cling to precipitous hillsides. After lunch, old men sit in the meagre shade of trees and smoke. All the while, the island is alive with cicadas. They chatter all day in a raucous chorus that never stops, resounding all around in a cacophony of tones and clashing rhythms. After a day or two, I learned to tune it out, but occasionally I’d become suddenly, urgently conscious of the racket, and the world would explode again with sound. In the hour either side of sunset, when the heat was exquisite, the evening air grew heady with jasmine and lemon. The jumble of architecture felt strange and at times a little sad. The global crash hit Greece harder than most, and there are abandoned building sites everywhere. The skeletons of these half-formed houses cling to the hills and wrap themselves in vines. It’s an extraordinary place.

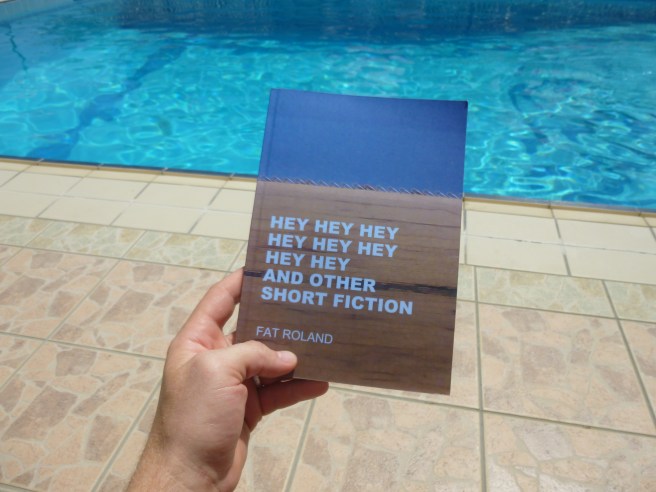

One of my favourite things about going on holiday is having the time to read. I’ve been reading a little more often in the last few months – trying not to work so late, and going to bed with a book instead – but on holiday, I can gorge myself. This time round, I went through The End Of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas, Thursbitch by Alan Garner, Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey by Fat Roland, The Coma by Alex Garland, It’s Lovely To Be Here by James Yorkston, Bring Up The Bodies by Hilary Mantel and The Evil Seed by Joanne Harris.

I love Joanne Harris, but struggled to get into The Evil Seed. As Harris explains in her introduction, it was her first novel, and she doesn’t feel she was firing on all cylinders. I found the regular switch of narrators a little jarring, for all that her writing was as wonderful as ever. Harris is a master, but The Evil Seed simply wasn’t for me. I also struggled with The End Of Mr Y. It started well, with a great premise – in a second-hand bookshop, a research student discovers a novel no one has seen in a hundred years. The book is supposed to be cursed – anyone who reads it will die. What a brilliant idea for a novel! Scarlett Thomas is extremely good at explaining the complex scientific theories that underpin the book, but as the plot unfolds, The End Of Mr Y felt increasingly like a collection of philosophical discussions tacked together with incidental actions. It was too disjointed for me – no flow.

I bought The Coma by Alex Garland years ago, and have been saving it until I finished writing The Year Of The Whale – because Garland’s book is also an illustrated novella, which is how I’d like The Whale to appear, if it ever does. It’s another good premise – a man exploring his own coma for meaning about his life – but one that is better managed in Marabou Stork Nightmares by Irvine Welsh or The Bridge by Iain Banks. Using minimal text, Garland brilliantly navigates his way around the dreamworld of the coma, wonderfully abetted by stark, startling woodcuts, but the final sequences became convoluted and disjointed with exposition, breaking an otherwise immersive experience. It was a shame, on finishing the novella, to realise that it came to a little less than the sum of its excellent parts.

Now we come to Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey, the second collection of flash fiction by Fat Roland. Disclaimer: I know and like Fats. I hope that won’t detract from my review of an excellent collection of shorter stories. Fats tends towards the weird in his work – or the really weird, in fact – often working with the mundane to expose the inherent strangeness of this grand and rolling shambles we call life. And he’s extremely good at it, too. Hey Hey Hey is a generally very strong collection, but some of the stories are exceptional: stand-outs for me were The Listener, and Michael Is A Horse, A Beautiful Horse, which rank amongst the best flash pieces I’ve ever read. I preferred Hey Hey Hey to his first collection; although Andropiean Galactic Lego Set Blues is also good, this second collection feels more assured in its use and abuse of the surreal, more convincing. It’s funny, chilling and thrilling, all at once.

Several of the stories are about swimming pools, and then I noticed this. Curious, no?

Several of the stories are about swimming pools, and then I noticed this. Curious, no?

It’s Lovely To Be Here is a collection of James Yorkston’s touring diaries. For those lucky individuals who have still to discover James Yorkston, he sounds like this:

…and he’s one of my favourite musicians. I’ve seen him play three times – by accident at The Raigmore Motel in Inverness back in 2001, I think, supported by Malcolm Middleton, though it may have been the other way round; then with his full band at The Brewery a couple of years ago, which is one my all-time top gigs; and then solo at The Dukes in Lancaster last year. He’s brilliant live, and these diaries – witty, honest, funny, poignant and a little sly – give a compelling insight into the flip side of life as a touring musician. I guess it gave me pause to think of the times I’ve approached him (or other musicians) after a gig, gushing praise and wishing well. Especially now I’ve started performing my stories live (nowhere near the same experience, but in the same universe, I suppose), I better appreciate that sometimes that’s the last thing a performer wants – to be inundated with people, and all the psychic tension and expectations they bring with them, when they’d rather go to bed. These diaries are funny and wickedly honest.

I never planned on reading Bring Up The Bodies by Hilary Mantel. I absolutely hated Beyond Black, the only other Mantel novel I’d tried, and I was therefore cynical about the praise heaped on this book and its precedent, Wolf Hall. But when I’d finished all the books I’d brought with me, I had to turn to the graveyard of dog-eared abandoned holiday reads in the hotel. Bring Up The Bodies was the only one I even halfway fancied, though I started reading with reluctance. And do you know what? It’s magnificent. Set in the court of Henry VIII, it plays out the last few months of the life of Anne Boleyn from the perspective of Thomas Cromwell, the king’s fixer. Bizarrely, Bring Up The Bodies actually gave me what I was expecting, but failed to find, in George R R Martin’s Song Of Ice And Fire – thrilling, page-turning intrigue on the price of power and the rise and fall of dynasties. It reads like The Godfather. Mantel’s Cromwell is an absolutely astounding narrator. I’m definitely going to seek out Wolf Hall, now, and I was delighted to see in the author’s note that she has more plans for Cromwell.

Finally, there’s Thursbitch by Alan Garner. I’m relatively new to Garner, off the back of his wonderful collection of British Fairy Tales and his short novel Strandloper, though I probably read The Owl Service when I was a kid. I’m still digesting Thursbitch. It’s profound and important, but it isn’t much fun. Garner creates worlds real enough to touch. His prose is so sparse, his stories so lean, that it often feels like there’s nothing there at all – as though his work is invisible, and his books are slices in time, windows into centuries when the world was young and hungry, and land still mattered. Thursbitch is about an old magic, a northern magic of white hares and white bulls and bees, of toadstools and snakes. It’s almost voodoo. A magic of the stones and the seasons and the night sky and the bog. It’s a magic of balance – of keeping the land and the people in check, pragmatic, without mysticism or spirituality. It’s heady stuff, and I’m still reeling. Like Strandloper, it’s dense, often using language so archaic it feels alien, and Garner gives nothing for free. I’ll read it again in a few years, I think, and see how it’s changed – how I’ve changed.

Back into pre-wedding mania. The garden has bloomed without us. The Black-eyed Susan has climbed to the top of the trellis, and the Russian vine is turning into a triffid. They remind me of the plants that explode everywhere in Kefalonia, wild and reckless in the dust and dirt. It’s strange to come home. Mon and I talk a lot about living abroad. I get depressed by the daily horrors this government continues to inflict on anyone who isn’t already rich, and I harbour visions of growing my own peppers and onions and garlic and chillies. We talk of Spain and France. Of a simpler life, I suppose, where we’re not drowning in screens and SATs. One where I can write and Mon can paint and Dora can chase katydids in the pear trees. There are times it feels like a boy’s dream, to run away, and times it feels like the brightest, broadest road we could take.

Halfway through the holiday, there was an insect drowning in the pool. It was my turn to rescue it, so I slipped into the water, swam across and scooped it out on the end of one of Dora’s toys. It was a honeybee. It dried in an instant and flew away, and I swam back to the edge of the pool. Just before I clambered out, I spotted something and stopped. It was a speck, no more than three millimetres long, but it was unmistakably a mantis, intricate and perfect as clockwork. I’d never seen one in the wild. I called Mon across to have a look. Even as we watched, it flexed its killer forelegs, snap snap, and marched across the baking tiles, three millimetres tall and a king of the world. The day before, driving back from the cove at Petanoi, Mon saw a golden eagle.

I love Cumbria, but there’s a splinter in my head that says we could be living cleaner, should be living simpler. Living slow.

Coffee, Cake & Crime

I’m delighted to share my interview with crime blog There’s Been A Murder. Read on for some thoughts on The Visitors, writing characters from real life, my next projects and (gulp) my attempt at some writing advice…

The interview is here.

This one book – Henry Sugar

A couple of weeks ago, Daniel Carpenter came up with the idea to blog about a book that changed everything he knew about reading and writing, then pass the baton onto others. He wrote, brilliantly, about The Wasp Factory, then nominated David Hartley and myself to continue the chain. David wrote, promptly and also brilliantly, about Frankenstein, then picked Benjamin Judge and Nija Dalal to follow. Benjamin Judge (seriously: who is Benjamin Judge? I’ve read in Manchester three times, and never met him. He’s either a front, Lawnmower Man, or a ghost) then wrote with intimidating speed and grace about Tom Clancy’s Red Storm Rising, which means I’m late and under pressure.

The brief is to write about a book that changed the way I understood literature – that made me realise “what writing could do”. That’s a tough call. My first instinct was also for The Wasp Factory, which had a massive impact on me. But I think, on reflection, that others that hit me deeper, if not harder, and I can’t come close to Dan’s thoughts on what remains an astonishing book. I’ve spent a lot of time weighing up what to write about instead. Fingersmith by Sarah Waters is my biggest recent influence, but that was more like rebalancing my compass. Bruce Chatwin’s Songlines shook me to my core, and Jasper Fforde’s Bookworld series changed the way I thought about stories. Before that, the Harry Potter books got me reading again after a long period of not reading at all.

In the first draft of this post, I wrote 500 words about The Proud Highway by Hunter S. Thompson. The first scintillating volume of his letters was the inspiration that started me blogging while I was backpacking in Australia; that blog taught me to write (albeit like him), which led to a job in magazine journalism, which led to me writing fiction in my words of my own…

I love Hunter S. Thompson. He remains an inspiration for his sheer, indomitable rage against the greed, corruption, insanity and monstrous terror of corporate government. His prose is flawless, and The Proud Highway was the book that definitively led me to becoming a writer.

But – having written 500 words about Thompson and his letters – I stopped short. A book I hadn’t thought about for years swum into my head, and I knew it mattered more. It’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (and Six More) by Roald Dahl. I don’t know when I first read Henry Sugar, but I think it was during the single year I spent in an Edinburgh boarding school while my parents lived in Germany.

I remember almost nothing before the age of 10 or 11, and my time at the boarding school sneaks up on me like spidersilk – fleeting, single strands, flickering with light, then gone. And although I don’t remember exactly, I know that I spent a lot of time in the school library. I know I read King Solomon’s Mines, and all The Hardy Boys books, and a bunch of Stephen Kings. I would have read Dahl’s children’s fiction when I was younger, but I’m pretty sure that was when I stumbled upon his more adult stories.

I rediscovered Dahl when I was in my early twenties. I found all his works in a charity shop in London, and bought the lot. I gorged on them. His stories are consistently excellent, but Henry Sugar is the strongest of many extraordinary collections. The tale of the boy and the turtle, or the mysterious hitchhiker, or the greedy landowner and the treasure hoard, or the title story, all explore the no-man’s-land, the thin threshold between the real and the impossible. They are all perfect stories, delivering just desserts to protagonists and antagonists alike. Another of the pieces, The Swan, haunts me still; Dahl’s tale of bullies brutalising a class loner is gut-wrenching, brilliant, beautiful, devastatingly sad and entirely magical.

Henry Sugar is ferocious. But how does it redefine my idea of what books can do? It didn’t have that impact on me as a child, certainly, because I had no concept of books doing anything other than taking me away – I simply read and read. But in my twenties, on rereading Henry Sugar, the ghost of it flooded back – the sad magic of The Swan sluiced through me, and it was utterly transporting. Where Sarah Waters holds back from explicit fantasy, and Neil Gaiman commits to it completely, The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar perfectly inhabits that edgeland between reality and fantasy. This is important because I see, now, how I’m drawn to that same space in my own work. I don’t want to write like Roald Dahl – I couldn’t – but I’m trying to walk that same tightrope between two places. And in that sense, no other book has so changed the way I think about books – about writing – about reading – about living.

So that’s me. I’m going to nominate Iain Maloney and Ali Shaw to continue the series, though I haven’t asked them yet.

Flow

On a good writing day, I write 2,000 words. When I’m working well, that’s fairly consistent. Whether it’s 1,800 or 2,500, I always seem to end up in the ballpark of 2,000. In terms of quantity alone, a month of 2,000 word days is a 60,000 word manuscript (which is the philosophy of NaNoWriMo, of course).

Obviously there’s an awful lot more to it than that – 2,000 a day doesn’t include all the back-peddling, redrafting, tea, editing, notes, research, cursing, blogging (!), procrastination and rewriting – and it doesn’t include the bad days, when it’s a struggle to carve out 400 words. I have plenty of bad days as well, especially at the start of a new project, when I’m still feeling out my way, finding the right path. For context, I don’t believe that the key to good writing is simply writing and writing and writing until something mystic clicks and the good stuff comes pouring out – check out J. Robert Lennon’s ‘ass-in-the-chair canard’.

When I started writing The Visitors, it was completely plotted out. There were about thirty chapters, and each chapter had a paragraph, or maybe just a line, detailing what would happen. That plan became redundant within weeks, if not days. By the time I was even a quarter of the way through, my chief antagonist had switched to someone completely new, and the plot expanded hugely – the final draft has around sixty chapters. But the biggest changes lay in how the characters escaped me. As I wrote them – as I spent more time with them, and came to know them better – I realised they were evolving. They were doing things I hadn’t expected, but those things became inevitable and essential as their personalities developed. Their autonomy dictated their story. Once that happened, and they were set upon a path of their own making, the manuscript generated a momentum that I could not control. In the final two or three months, I’d regularly write 4,000 or 5,000 words in a session. On the last day of writing, I wrote 11,000 words in 14 hours. That surge, that flow, was intoxicating. I drowned in my characters, drowned in the island I’d created. The story became a gyre, and I was tumbled in the centre.

I’m now about 16,000 words into The Hollows. On each of my last four writing sessions, I’ve cut around 1,000 words, and written around new 1,000 words. The overall count isn’t changing much, but I think I’m making progress. I’ve learned a number of things along the way, about writing, and about myself. Because I had to go through such an excruciating redraft with The Visitors, I originally tried to plot out The Hollows as tightly as I could. Each chapter had multiple paragraphs and notes, with detailed ideas about the how the story would unfold. It was comprehensive. I was decided: this time round, the novel was going to write itself.

I should have known better. I raced off to a strong start, writing the first 10,000 words in three days. Then I applied to the Northern Writers’ Awards for funding towards a research trip. As part of the application, I had to include a synopsis of The Hollows. Seeing the plot condensed into a single page, I realised at once that the story was too tight. It had no room to breathe – I’d strangled it with structure. It was far too dense. I ditched all my planning and rewrote the synopsis for the purest story I wanted to tell – about a man who loses his memories, and the woman who goes to find them – and sent it off. I haven’t heard back yet, but regardless of how my application turns out, the process of writing a new synopsis was revelatory, and for that alone I’m grateful.

I want to start The Hollows right. Unravelling some of my first draft has been heavy going, but it’s important to me to know I’m on a better path. I’m getting there. I’m starting to meet my characters. I’d forgotten that I didn’t always know Flora, and Izzy, and Ailsa, and John – it took time to find out who they were. I’d forgotten, in the dizzying exhilaration of finishing The Visitors, that it wasn’t always so easy to write. The flow comes only after all the hard graft has been done.

On Friday, I finished my novella The Year of the Whale. That’s been five years in the making, including sessions when I’d struggle to chip away at 200 rotten words. But on Thursday, the day before my deadline, I soared through 5,000 words with joy in my heart. That was the flow, and I’d forgotten how it felt. I’d forgotten that I could feel so engrossed in my stories – that I could drown. That’s where I want to get to with The Hollows. That’s how I want to finish, whether it’s in six months or one year or two years’ time. But I know, now, that all the graft comes first.

My friend Ali Shaw believes you can’t know if a novel will go all the way until you hit 20,000 words. Author Matt Haig feels the same, but his mark is 40,000. Word counts only matter for the person counting. Like climbing grades, they measure nothing but an individual’s own sense of progress. They are a poor measure, perhaps, but they are all I have to mark my way: yan, tan, tethera.

The Hollows has been stuck on 16,000 words for weeks, despite long, hard days of work. I haven’t enjoyed that. I crave that sense of flow, when everything makes perfect sense. When I had that moment in The Visitors, I described it as a ‘glittering open highway’. I suspect I’m still a long way off reaching that highway in The Hollows, but it has truly settled me, on completing The Year of the Whale, to remember that the flow comes from the writing – not from the writer. From the story, and not the storyteller. For all the times I beat myself up about not working hard enough, not writing fast enough, not doing more – finishing that novella has been a gift. It has helped me remember why I write. I write to drown. To drown, I need the gyre. To make the gyre, first I have to fill an ocean.