National Storytelling Week is here! The theme this year is ‘Speaking Story Into The Darkness’ – and the Society For Storytelling have asked for 90-second videos on the theme. Here’s my effort – it’s a story from the Arctic Circle that means a lot to me. Enjoy!

Tag: folk

Fox Woman

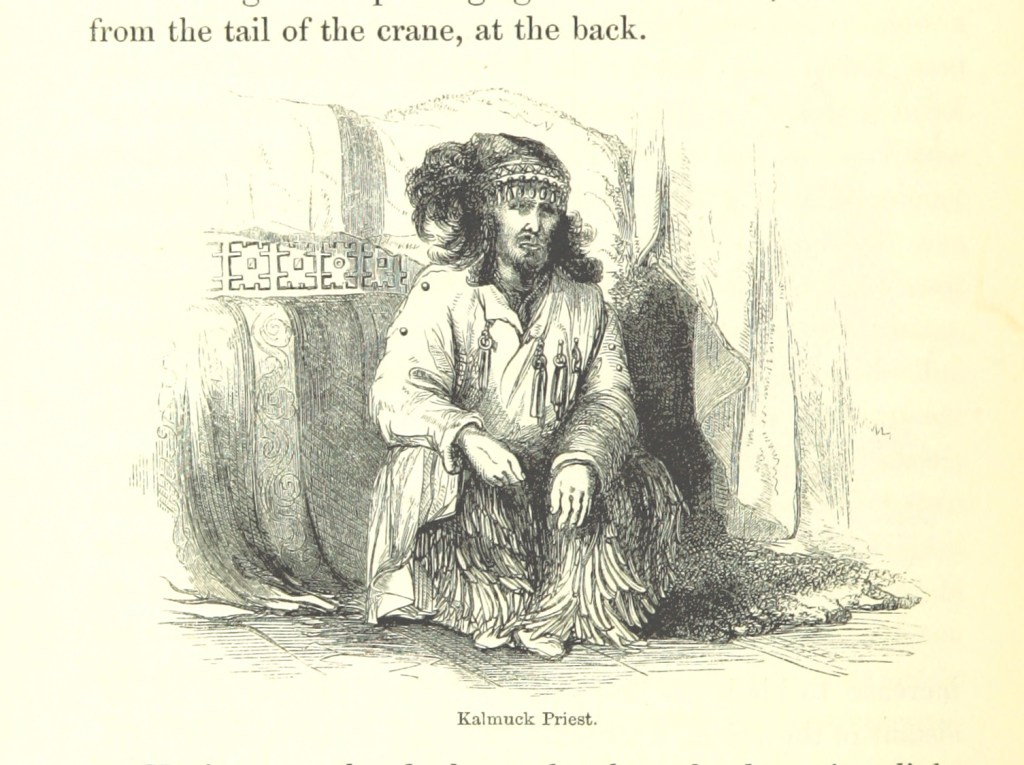

Another tale, another telling; at my last story circle, I performed a Siberian folktale called The One-Eyed Man & The Fox Woman from a wonderful collection called The Sun Maiden And The Crescent Moon by James Riordan. It’s a story I first heard on a podcast told by Daniel Deardorff. By way of drums and dreams he seized me by the scruff and never let me go; when I started storytelling, The Fox Woman was right at the top of my list of pieces to learn. It’s longer than Gobbleknoll or The Talking Skull, about 20 minutes or so, and I’ve been working my way up to it by way of shorter tales.

There’s an otherworldiness to this one. The titular One-Eyed Man is a pretty small part of the story – the journey belongs entirely to the Fox Woman – her anger, her longing, her choices, her consequences. It holds at its heart a crystal truth about moving through life; about what a person should tolerate, and what they cannot. It’s about ageing, changing, desire, belonging and peace. It’s vast and it’s wild.

The Siberian stories are strong. I’m currently reading The Turnip Princess by Franz Xaver Von Schonwerth: 72 folktales and fairy stories collected roughly in parallel to the Grimms, then lost for over a century in a city archive. As with my recent reading of some Russian stories, I’ve been struck by how many of them are structurally quite weak; elements appear at random with successions of unconvincing ‘and thens’ disconnected from what’s already happened. What I admire in the Siberian stories (as with Inuit stories) is that most elements of the story happen because of something else – the magic remains wild and vital, but the threads of story are causal and connected, rather than consecutive – at times almost random. As a side note, it’s fascinating to see the movement of stories through time and place – there are quite obviously elements of Grimms throughout The Turnip Princess, then what crops up but half of Three Golden Heads Of The Well? (Another story high on my list to learn.)

I’m off topic. Back to Siberia. The stories are rich in blood and fat and sinew. Eating, not eating; animals that talk to people; the Moon sneaking down by night to steal a bride; clayman, raven, elk. Animals are completely and vitally integrated with people – survival depends on food, and food is meat, and meat is animals, and animals is hunting. This is the prism through which almost every story plays out; from the mythic to the domestic, tales of tooth and blade and fur and fire. Odd thing for a vegetarian to say, but count me in. I’m there.

Telling The Fox Woman went well, I think, I hope. Ten of us met in an old Quaker graveyard high on Fellside, looking out across the town, with a large ginger cat slinking through the long grass, and the last of the summer swifts high overhead, and a robin ferreting through wild blackberries. I brought in repeated motifs to bookend the story, and that seemed to go well; one of the jokes didn’t land at all, but the other landed superbly. I extended the scene with the baskets of skins, which felt to me to make sense to the story, and I removed the scene with the reflection in the pool. I managed not to rush – to slow down and relish the flow of words. I’m increasingly drawing on my well of prose and poetry when conjuring the images. I still have a very long way to go in using my body and voice and face, and this is something to work on.

Next telling is at the Brewery open mic supporting Rose Condo – either a Zen koan called Two Tigers & A Strawberry or Queen Albine, depending on how angry I am on the night about English nationalism. Chances are I’ll be quite angry.

Gobbleknoll

.

There was a great grey lump of a hill that ate people…

…and Rabbit’s Grandmother told him never to go there, and Rabbit being Rabbit he went there as soon as he could, and he thundered his paw on the flank of that hill and called out, ‘Ho! Ho, Gobbleknoll! Open up! Show yourself! I want a word with you…’

…but Gobbleknoll knew Rabbit was trouble, and Gobbleknoll stayed shut.

So begins Gobbleknoll, a short folktale I came across in an Alan Garner collection and originally from the Sioux people. I performed it at the Brewery open mic last night, making for my first public telling, and first time performing since the Stealing Thunder storytelling course.

I added some bits and removed some bits – an extra beat in the middle, and a tweak to the end. Stories evolve. They flow like water from person to person to person, always changing and yet always water. I loved giving the story space to breathe – feeling it settle into the contours and corners of the room. It seemed to go over okay – lots of people spoke to me at the interval or after – most simply stating how good it was to hear a folktale. Adults aren’t given many opportunities to be children, and that’s one of the great gifts of storytelling. Storytelling shuts the door on the scream of life, if only for a moment.

Next up I’m reuniting with my peers from the story course… we’re forming informally, meeting irregularly in a circle to share new work. I’m preparing a story called The Magic Bowls for that one – it has the most wonderful twist.

Storytelling then. Feels like I’ve begun. If I get the chance, I’ll record my take on Gobbleknoll and pop the audio on here.

Open up.

I want a word with you.

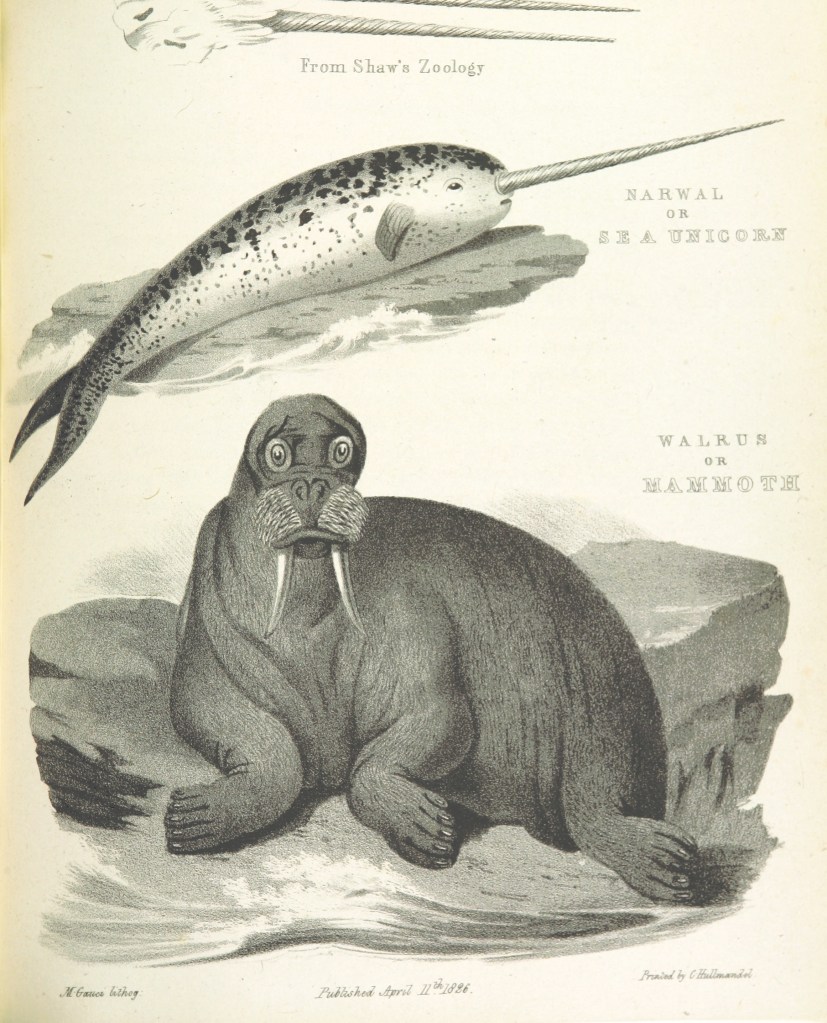

Always, always, always the sea

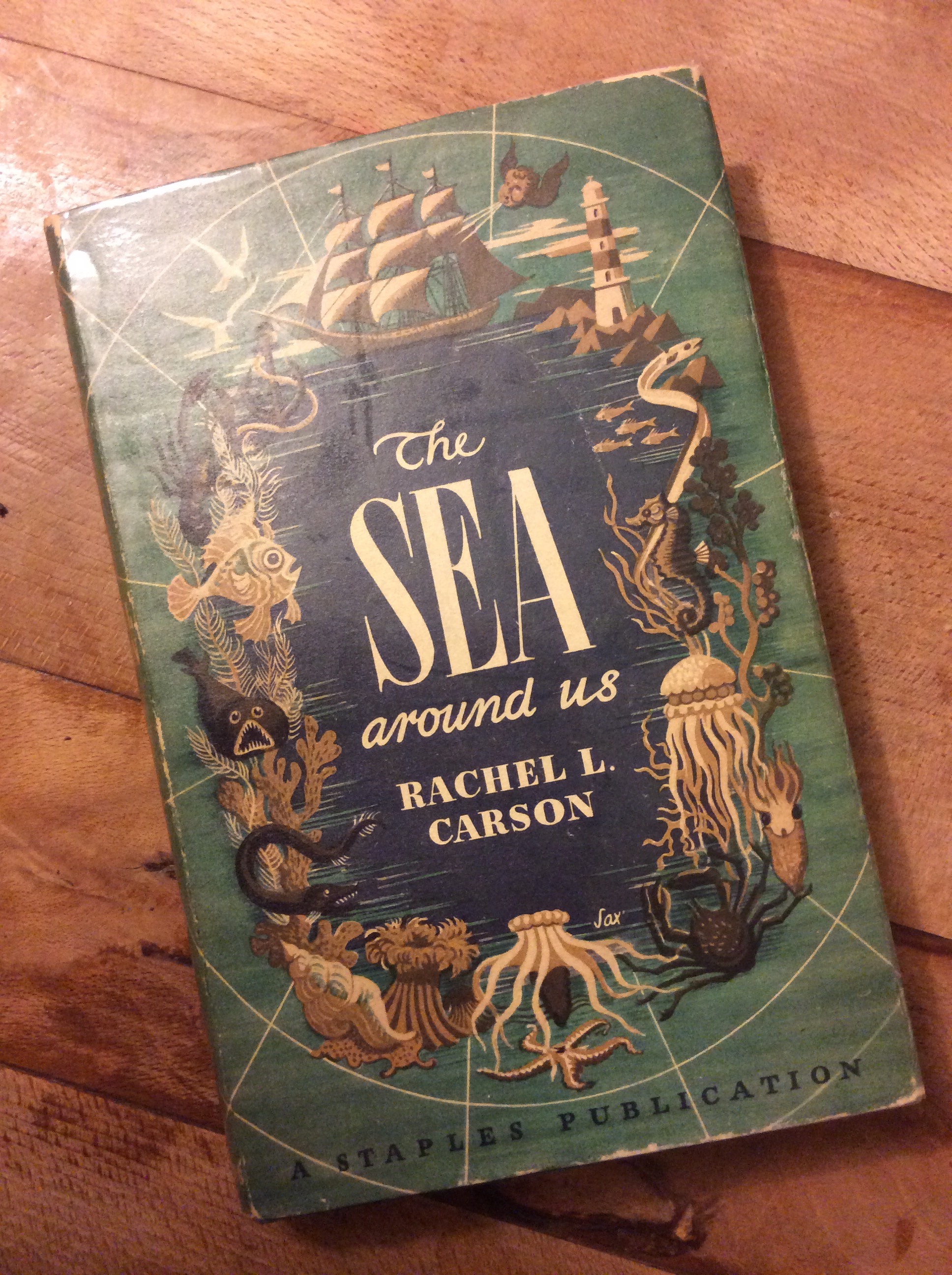

I’ve been thinking a lot about the sea, lately — I was lucky to be given several books about the sea for Christmas presents, and then my excellent wife tracked this stunner down for me too —

The next story I write will be about the sea — the idea fell into my head, perfect as a cowrie, while I was working on the closing chapters of my last book. And although I was planning another novel altogether for my next one, the sea book has overtaken it. I’m excited.

I’m desperately trying to finish off a film edit right now, so bear with me — I’ll write more about the sea another time. For now, I’ll leave you with this — a quick mix I threw together of ocean songs, featuring British Sea Power, Bat For Lashes, Modest Mouse, Frightened Rabbit, James Yorkston, The Waterboys and many more. Enjoy.

A business of wrens

I’ve been making good progress on the book in the last two weeks, so I’m allowing myself a wee break to write about collective nouns. I love collective nouns. There’s something about them, at once melancholy and sweet — an innocence — that I find utterly beguiling. We all know prides of lions and herds of cows, but the rare ones are better, because they’re strange and odd and upside-down. In his heartbreaking new album Skeleton Tree, Nick Cave sings about a charm of hummingbirds. A week or so ago, researching a story about birds, I wrote of murders and murmurations, wakes and gulps, springs and flings, scolds and pantheons.

A good collective noun needs to personify some characteristic of the collection, rather than simply iterate what the noun is or does. My favourite collective noun is a drift of swifts — the sheer simplicity of the rhyme, the soaring swing of the swifts as they zip around the house in the sheerest of circles.

In the new book, I wrote of a pocketful of jackdaws. I didn’t think a thing of it until reading the chapter back, later on, and wondering where it had come from. Then I decided to ask people to make up some collective nouns of their own. This was only a few days after Trump had been elected, and around a third of the responses were basically ‘a bastard of Trumps’ or similar. Here are some of mine, on the left, and my favourites from the folk who joined in on the right:

A pocketful of jackdaws

A compass of clouds

A misery of clowns

A duplicity of toads

An orchestra of bees

A clarity of cats

A spindle of witches

A philosophy of starlings

An orbit of angels

A kerfuffle of mice

A haunting of pike

A cathedral of jellyfish

A parley of pirates

A calamity of bats

A knot of weasels

A panic of pigeons

A snippet of crones

A juice of pumas

A punnet of fucks

A scuttle of rats

A tangle of sparrows

A sundial of shadows

A shower of seedlings

A murmur of dreams

A wheeze of bagpipers

A choir of carnations

An apprehension of streetlights

A bribe of winkles

There were many more — I couldn’t include them all. There’s something in a good collective noun that elevates the noun itself, or reveals another side of its nature. Some of these are so obvious they should fit into daily use — ‘Pigeons exploded in their panics, clattering about the station roof’ — and others are more abstract. There’s no particular reason, for instance, why ‘a juice of pumas’ should work, but somehow, it does — ‘One by one, a juice of pumas slipped from the gloom and gathered near the tracks.’

What are your favourite collective nouns? And what would you invent for a new one?

Mirror mirror

Earlier today, my heart broke. I’ve been working on my second novel, The Hollows, for almost exactly a year – I started it on Christmas Eve 2013, though I couldn’t write for half the year. I’m now 30,000 words into my first draft. It’s excruciatingly hard to write this, but I’m about to change it all. The reason is the best-selling author Kate Mosse, who appears to have written my book already. I haven’t read it, but her latest novel, The Taxidermist’s Daughter, explores the same themes of memory – suppressed, regressed and rediscovered – as The Hollows. Her novel revolves around a father-daughter dynamic, like The Hollows. Her novel is set in a huge marsh, like The Hollows. I could handle all of that. I’d guess that was true of lots of novels. But today, I also discovered that the lead character of The Taxidermist’s Daughter has no early memories after a traumatic childhood experience; that a modern crime begins to unlock those hidden memories; and that the unlocking of those memories reopens the wounds of an old injustice. That was basically the plot of The Hollows. I’m heartbroken, because I was finally beginning to gain some traction. It was finally starting to move, but I can’t stomach those similarities. It’s too close. It’s no good.

I’m not going to start again, because I’ve written some good stuff. But I am going to change it radically. That means significant cuts – again – and it means the whole enterprise will take longer than I’d hoped, and that’s devastating. I was almost halfway through, and now I’m back to the beginning. I can’t just get hold of The Taxidermist’s Daughter, read it, and rewrite around it; no story is built from omission, and the thought of it makes me sick. But it does mean revisiting the crossroads I discussed last week, and taking another path. It hurts, and I’ll set out with heavy heart, but I know, with every fibre of my being, that I’m nourishing the kernel of a good story, and I’m not going to let it go.

Whales, mandolins and singing bottles… and once again, I find myself staggered at how my stories hurt me.

Little Dog Turpie

My wife showed this to me, not long after we met. It’s one of the ways I knew she was the girl for me. An authentically gruesome spin on the old folk tale of The Hobyahs, here’s the tale of Little Dog Turpie.

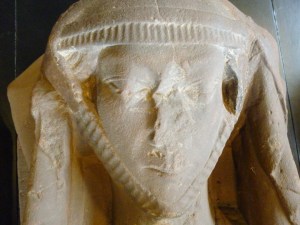

The Abbey

I visited the awe-inspiring Furness Abbey last week. It’s one of those places that I find very hard to describe, and although I’m going to try, I don’t feel I’ll come close, so I’ll probably keep this fairly short.

The abbey lies in ruins, but the utter majesty of the place remains. Sandstone soars into the sky in towers, even as the wind and rain carve it back down into organic shapes. It’s humbling beyond measure to walk the grounds, to sit in the buttery, to peer up tiny spiral staircases, to measure spans and arches – to walk the same paths the monks would have walked, centuries ago. A watercourse trickles through the ruins, tight with brick and riddled with tunnels and drains, but also dense with willowherb. It makes the abbey seem both antique and feral. There are plants trickling from upper ledges, and swallows nesting in the cells. There are tunnels and alcoves and windows and doors. What survives of the former halls still feels enclosed. Parts of the abbey are completely removed from the main walkways, and it’s unnerving to stand in silence and stillness and reflect on the hundreds of lives to pass through the same space. It’s crawling with ghosts. They’re in every stone, in every blade of grass. The site is surrounded by trees that hush in the wind, and the place is full of whispers. It embodies that sense of threshold I feel so drawn to. There are blind corners, where the space is shut abruptly out and your skin crawls with presence. Gravity weighs more in the abbey. The stones have grown gaunt on life and death and time.

Time. That’s the abbey means. The whole place aches and creaks with a ferocious sense of time. It’s massive. It echoes, it rebounds from the rock, from the moss. Walking the walls brings our few moments in this world into ferocious, ridiculous focus. It’s magnificent. It’s extraordinary. Go and explore it for yourself.

The Year of the Whale

Last night, with slightly more than an hour to go before the deadline of the MMU Novella Competition, I finally finished my novella The Year of the Whale. The image above is a randomised cloud of the most common words in the manuscript, which is a really satisfying way to look back on what I’ve made.

I started writing it in 2009, and it has spent entire years untouched, waiting for attention in the dusty recesses of my hard drive. It’s written in first person with a very particular voice, and it’s been strange to return to it so sporadically over the years, and take up the mantle of that voice again. I’ve wanted to finish it for a long time – it was one of my New Year’s resolutions, no less – and I’m thankful to the competition for giving me the spark to get it done. I don’t expect anything to come of it – that way madness lies – but I’m thrilled to have wrapped it up last.

The Year of the Whale is the story of a man called Henry Cowx. He is a fisherman and walking guide in Morecambe Bay, riddled with arthritis and wracked with guilt. His story explores that guilt, and gives some quiet thought to what it means to remember. It’s about walking and place and ghosts and folk tales, and our connections with the land. It’s at the heart of my obsession with threshold spaces. It’s a meditative, elegiac story, and a long way from where I’d like to develop my work – but Henry has never been far from my mind, and I’m glad to give him closure at last.

I discussed some of the genesis of the story in my Thievery post for Kirsty Logan.

I’m working my way through some film jobs at the moment, but it’s almost time to get back into The Hollows.

The Sprint Mill Sessions

I love this: my friend Dom has been filming the grassroots Cumbrian folk scene. Last summer he gathered dozens of people for a campfire session at Sprint Mill, and this was the result – young musicians, sharing their songs by firelight. The sessions so far can be found right here, but I’ll leave you with Paddy Rogan and The Way You Used To Do…